Traditional Pub Scam and Self Pub Plan: Ditching Gatekeepers for Profit, Control, and Sanity

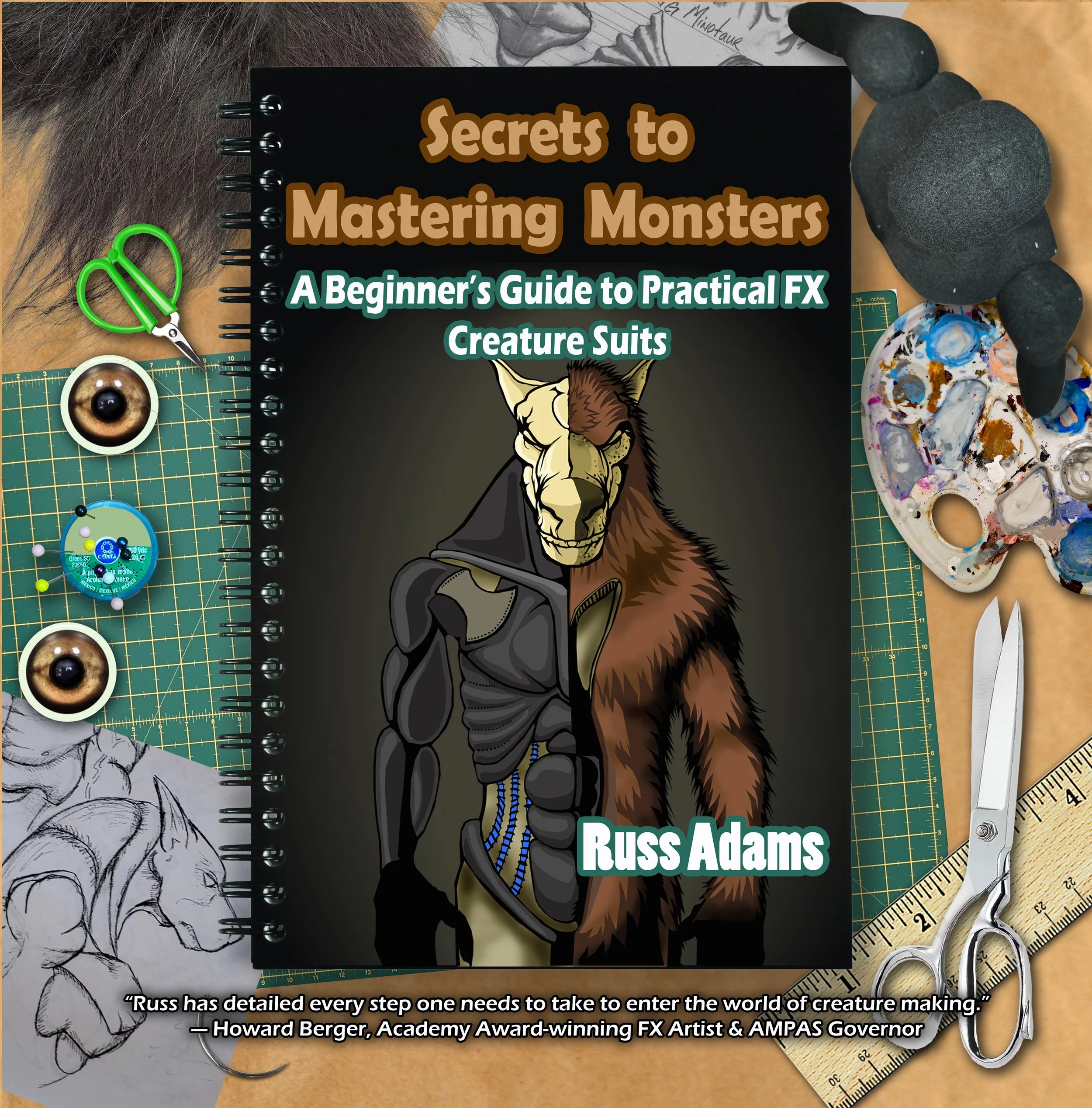

Let me start by saying this: I’ve self-published six titles. Five of them are how-to books on some pretty niche topics—special effects, creature suits, action figures, that kind of thing. The sixth? An exposé on reality television and my time on one of those shows. And no, I didn’t take the self-publishing route because I couldn’t cut it with a “real” publisher. I went the traditional route first. And that experience is exactly why I said to hell with it and went independent.

Right after the season one finale of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop Challenge aired, I was invited to dinner at a comic con by a publisher and some of his authors. They were fascinated by my time on reality TV—and I had a pitch ready. A book that gave a real behind-the-scenes look at reality television from someone who’d actually lived it.

They loved it. Within weeks, I had the green light to write. Since I’d already outlined the book ahead of time, I turned in the manuscript fast. Everything was moving—until it wasn’t. The publisher’s legal team got nervous about my non-disclosure agreement with the network. Everyone agreed the clause wasn’t enforceable, but this wasn’t one of the big five publishers. They didn’t have the war chest to test that theory in court. At the same time, my assigned editor was apparently causing issues behind the scenes. He was fired, and word was that every project he’d brought in—including mine—got shelved. The book was just weeks from print.

I got my rights back, thankfully, and started shopping the book again. Found another publisher—smaller, but with a few noteworthy titles. But things dragged on. One excuse after another, until I learned the truth: the head of the company was being sued for elder abuse. Not exactly the kind of stability I wanted in a publishing partner.

Then came publisher number three—my original editor, now launching his own press. I thought, maybe third time’s the charm. Big mistake. This guy turned out to be the poster child for amateur hour. He decided to release a limited edition hardcover—with dust jackets, no less—but botched the entire print run. A blank page had been inserted randomly, throwing off the pagination and flipping chapters out of order. And where the legal copyright page should’ve gone? A placeholder with “Insert legal copy here.” When I pointed it out, he laughed and called it a “collector’s item.” That was the moment I said, “I’m done.” I self-published the book myself—years after first writing it.

And you know what? I’ve never looked back.

What I’ve come to realize, after years in this business, is that traditional publishing is often a polished scam. People still treat it like the gold standard. Like it’s the only legitimate path. But here’s the truth: based on industry data, somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 first-time authors submit to agents or publishers each year. Let’s call it 60,000. Of those, about one percent—around 600 people—actually get accepted. The rest? Rejected. And worse, 50 to 67 percent of those submissions are never even read. It’s not about merit. It’s about luck. Were you lucky enough to land on top of some overworked intern’s reading pile?

There’s a lingering bias in the publishing world. A stink that says if a gatekeeper didn’t choose you—agent, editor, publisher—then your work must not be worthy. And if you publish yourself, it must be out of vanity.

Let’s call that what it is: a double standard.

Because the truth is, traditional publishing isn’t the dream most people think it is. If you get in, maybe you’ll get a small advance—maybe not. But you are handing over the rights to your work. Your title, your cover, your pricing, your marketing strategy—none of that is really up to you. Royalties? You’re probably getting 5% to 15% of the list price, after your agent takes their cut. On a $20 book, you’re lucky to see a buck or two per sale.

Meanwhile, self-publishing has changed. It’s not about vanity presses anymore. Today’s self-published authors are doing everything publishers used to do: hiring professional editors, commissioning custom cover art, running ads, setting global prices, and distributing worldwide. The difference? They keep 70% of the profits. That same $20 book now earns the author $14.

And still, people act like self-publishing is a fallback. Like it’s Plan B.

What drives me nuts is this: self-published authors do everything a traditional publisher would’ve made them do anyway. Build their own audience. Promote their own book. Market themselves. And if the book doesn’t catch on? They can pivot. Change the cover. Update the blurb. Rerun ads. Try again. Traditional publishing doesn’t give you that flexibility. You get one shot. Maybe 90 days on a shelf before your title gets pulled.

Self-publishing doesn’t guarantee success. But neither does traditional publishing. The difference is, one gives you control and ownership. The other gives you the illusion of prestige—and pennies.

So why are we still calling it “vanity” to bet on yourself?

It’s not vanity. It’s just business. And for a growing number of authors, it’s the smarter business to be in.

Let’s look at the numbers. Say 60,000 first-time authors each choose a path—one traditional, one self-published. Only 600 will break into traditional publishing. Of those, maybe six will hit bestseller status and sell more than 50,000 copies. Around 75 will sell between 10,000 and 50,000. About 130 might land in the 5,000 to 9,999 range, another 130 will sell between 1,000 and 4,999, and roughly 100 will sell 500 to 999 copies. Very few will sell under 500, because publishers rarely bet on titles they don’t believe will perform at least modestly.

Now let’s talk self-publishing. All 60,000 get their books to market. The results are more volatile. Around 24,000 to 30,000 will sell fewer than 500 copies. Another 9,000 to 12,000 might sell 500 to 999, and a similar number could fall into the 1,000 to 4,999 range. But here’s the interesting part: 1,800 to 3,000 authors will sell over 5,000 copies. And between 30 to 60 of them will become bestsellers.

Let that sink in. You are more likely to sell 5,000 or more copies of your book if you self-publish than if you go the traditional route. The odds are better. The potential income is higher. And the control stays with you.

Isn’t that what this is about? Selling books. Reaching readers. Making a bit of money while doing something you love.

To me, that’s not vanity. That’s common sense.

Research and Citations

Traditional Publishing: Odds and Realities

Alpha Book Publisher

"What Are the Odds of Getting Traditionally Published?"

Offers basic statistical context for traditional publishing acceptance rates.The Write Conversation

"The Woes of Unsolicited Manuscripts"

An editorial blog post discussing how many manuscripts never get read.Nathan Bransford

“What Literary Agents Do”

Former agent offers a clear breakdown of how the system works from the inside.

Financial Comparisons

Alpha Book Publisher (again)

Same post as above — includes average royalty expectations and income breakdowns.Nat Eliason’s Newsletter

“Why You Shouldn't Traditionally Publish Your Book”

A strong, data-backed opinion piece comparing traditional vs self-publishing income.

Self-Publishing: Reach and Revenue

WordsRated

“Self-Published Book Sales Statistics”

Deep dive into real sales numbers, income brackets, and success rates.Writing Forums

Community Thread: Latest Book Sales Stats

Informal, but reflects shared stats and experiences in the indie author space.

Me in the studio, tearing through my first how-to manuscript line by line, building a photo list to match every damn step. That shop was freezing, but I didn’t care. No gatekeepers. No bullshit. Just doing the work—my way.